Kahn & Arnold

Late 18th- first half of 19th Century: Changes are coming

Aron Kahn (1841-1926) and Albert Arnold (1844-1913) both came from rural Bavaria, where they peddled textile goods. In 1869, they moved to Augsburg (a midsize city near Munich) and founded a wholesale business specializing in cotton trade. Over the years, thanks to their entrepreneurial skills, the firm grew into a major cotton-spinning enterprise. The partners had gravitated to manufacturing partly because the social barriers to entering the new economic sectors were comparatively low.

Benno Arnold, Alfred Kahn, Eugen Oberdorfer. Photograph, 1891. Benno Arnold (1876-1944), left; Eugen Oberdorfer (1876-1943), right; Alfred Kahn (1876-1956) middle. Photo courtesy of Elisabeth Kahn.

Director’s villa on Remboldstraße 1, Augsburg. Photograph. Photo courtesy of Staatliches Textil- und Industriemuseum Augsburg (tim).

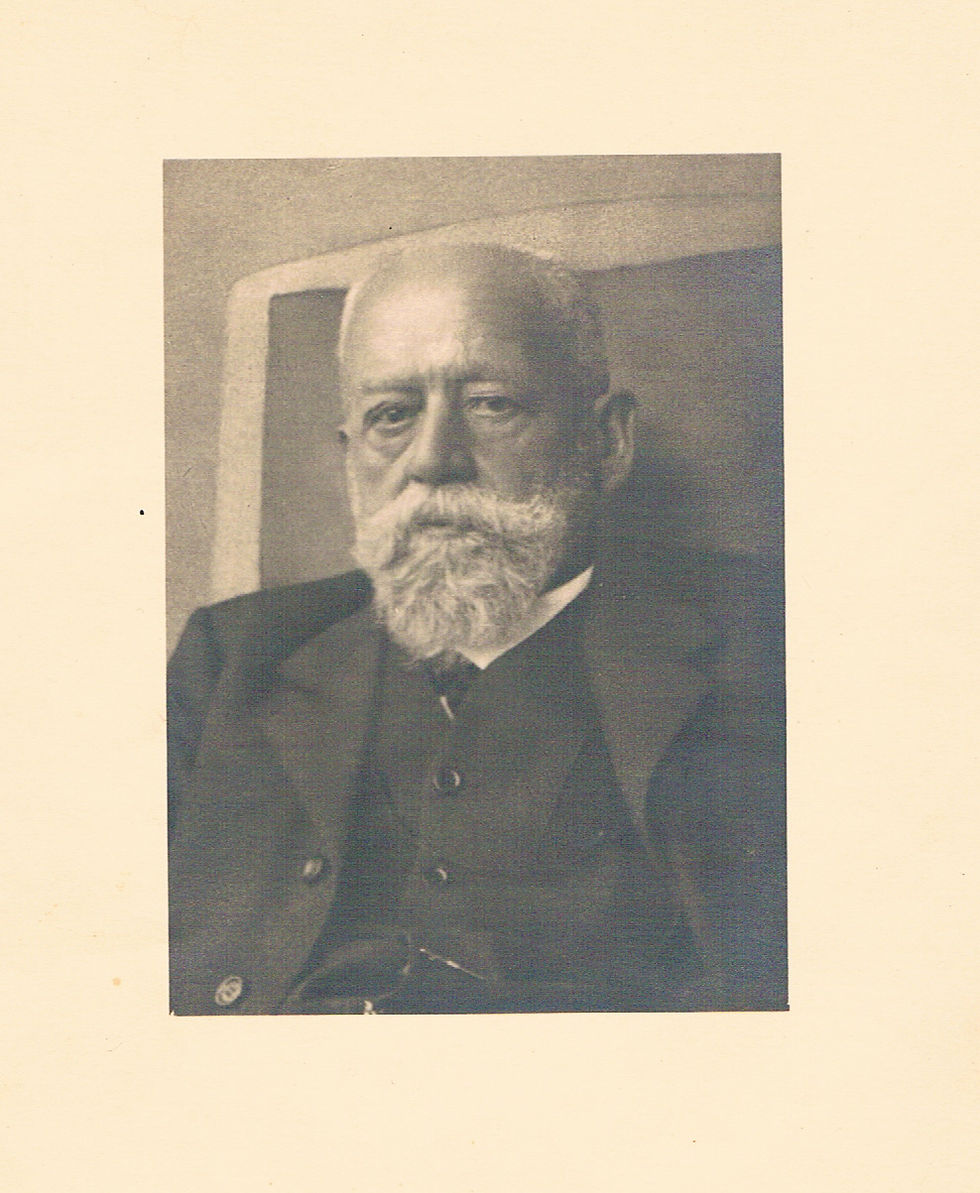

Aron Kahn (1841-1926). Photograph, framed, 1921. Photo coutrtesy of Elisabeth Kahn.

Aron Kahn's son, Ernst, was a successful banker and journalist in Frankfurt, and later wrote a memoir of his family.

Click here to view the digitized document in LBI's Collections.

Second half of the 19th Century: From entrepreneurs to major businesses

Although Aron Kahn and Albert Arnold‘s initial successes were in trading cotton, they soon recognized that the experience and knowledge they had gained over the years could be put to use in manufacturing. They purchased a weaving mill in 1885, shifting the focal point of their business away from trade into industrial production. Not only did they make improvements in the existing mill, but they also added a cotton-spinning mill. In the 1890s, moreover, they constructed a new high-rise spinning mill – modern and equipped with electric light, which increased productivity and made longer shifts possible, especially during the winter.

Spinnerei und Weberei am Sparrenlech. Graphic, Eckert & Pflug, Leipzig, 1900-1938. Photo courtesy of Staatliches Textil- und Industriemuseum Augsburg (tim).

Philanthropy and social justice

Perhaps influenced both by the Jewish tradition of giving and bourgeois patterns of philanthropy, members of the Arnold and Kahn families actively supported philanthropic endeavors in Augsburg. Motivated by the principle “Eigentum verpflichtet” (ownership has its responsibilities) and by good business practice, the firm provided employee benefits to its workers, such as disability support and supplemental benefits for pregnant employees. Hermine Arnold was active in distributing aid to the poor alongside other Jewish women.

1933 and beyond: From full-rights citizens to refugees and victims

The second generation of the entrepreneurial and respected Kahn & Arnold families in Augsburg fell victim to state-sanctioned persecution beginning in 1933. Like other Jews, family members were thrown off the boards of philanthropic organizations shortly after Hitler’s rise to power. Benno Arnold, who held a position on the Augsburg City Council since 1930, was forced out in April 1933. Benno also belonged to the Johannisverein (St. John’s Association), a charitable association that cared for people in need. In 1935, the association forced him out under the pretense that he had not paid his membership dues.

The highly successful textile firm of Kahn & Arnold had in 1923 rescued another textile firm, Neue Augsburger Kattunfabrik (NAK), from financial ruin and became its major shareholder in exchange for its financial assistance. In 1938, the company employed 940 employees and had its own savings bank for its employees and childcare facilities. In the same year, however, Kahn & Arnold and its interest in NAK were confiscated in the guise of a “voluntary” sale to the NAK. Some members of NAK’s top management had joined the Nazi Party to win support for the “Aryanization” of Kahn & Arnold.

Alfred Kahn (1884-1956). Photograph. Photo courtesy of Elisabeth Kahn.

Neue Augsburger Kattunfabrik. Graphic after 1885. Photo courtesy of State Textile and Industry Museum Augsburg.